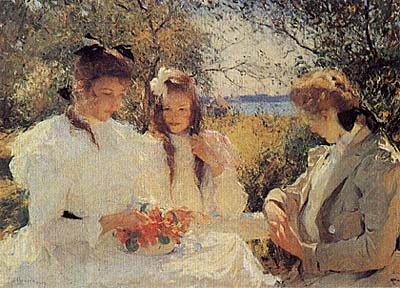

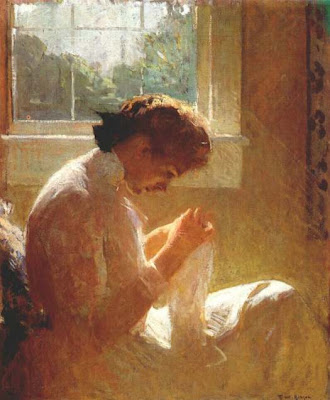

Advice on Painting from F. W. B. (Frank W. Benson) taken

after criticism by his daughter Eleanor Bedford (Scanned from an

original)

Thanks to Mary Minifie and Paul Ingbretson for

assembling and formatting the following text. I corrected some typos,

laid it out and added the images collected from the web.

THE CHALLENGE

"The

only fun in life is trying hard to do something you can't quite

accomplish. There is no real fun in accomplishing some definite fixed

thing.

"It is not easy. It is never easy. There is no

magic about it. It is just as much a science as the science of a doctor.

It has to be studied and worked at, and even then you never really

learn it. No one has any magic way of doing It. No one has anything to

start with except an over-mastering desire to do it, and the more you

have the desire, the more you will work at it and the more you will

learn. I am still working at it and learning, and that is all I care

about. I don't care about the pictures I have painted. I may become fond

of one and say "that's a good one", but all I really care about is

working at this thing, and it is still so far ahead of me that I shall

never reach it, and have only just begun to know anything about it.

SELF EDUCATION

"There

is no such thing as teaching a person anything. You may be helped

toward learning by a hint someone has given you, but anything you really

learn has got to be learned by experience and only by working and

solving the problem your self can anything become a part of your real

knowledge. Most people don't believe this, and want you to show them.

Showing them is like giving candy to a child. It doesn't help them at

all. They couldn't do it themselves and the next time they met the

problem they would not even recognize it. Most people think painting is a

God-given talent. It Isn't. It is a product of hard work and intense

mental effort and only those can succeed who have the capacity for work

and the necessary intelligence. (Said long before.)

“When

I was working in the studio in Paris the French Maitre who previously

had never been known to say anything to a student more complimentary

than "Pas mal", and that very seldom, said to me one day: "Vous avez le

metier dans le main; si vous jugerez mieux le caractere personelle de

votre models, vous deviendrez tres fort." There it is — Le metier dans

la main — your career is in your hand, to work out for yourself. No one

else can help you. But people will not believe this.

There

was dead silence in the room. It caused so much excitement that there

were crowds of students around my drawing all the rest of the morning."

(This was in the studio of M. Gustave Boulanger. The picture referred to

was the study of the head of an old bearded man. This picture was given

to Emerson Benson, cousin of F. W. B., and later Inherited by E. B. L.

and later given to her son, Ralph Lawson).

Me: "Thanks for the lecture"

FWB.: "All right. It won't do you a bit of good. You've got go dig these things out for yourself."

"The

only way to learn to paint is to paint, No matter how dissatisfied you

are with what you have done, you learn something. No one can tell you

things which you must learn from experience."

"My

belief lies in this direction—that you should learn absolutely to see

the thing truly as it exists, and then use that knowledge as you like. A

man should use his knowledge of this and express himself according to

his inclination, but beneath everything should be the solid foundation

of reality.

LIGHT AND SHADE

"The

important thing in painting is to keep everything as flat as possible.

Your tendency is to model surfaces too much, because you are looking for

effects of light and shade. Especially keep flat the less important

parts of a picture. Don't blend and soften too much. Where an edge cuts

sharply, make it sharp, with a flat value against the contrasting

background."

"You can't paint reality by just describing things. You must pay attention to light and shade and values.

"Look

continuously at the whole picture, not at parts, and roam from place to

place making adjustments. That's what painting is — Making adjustments.

Don't look at one part too long or you will paint it too much in

detail. The unimportant parts of a picture should not be minutely

described so that they will attract notice. Do the values and let it go.

Everyon - all of us — tries to get an effect by carefully describing an

object. That's not the way it's done. Go back again and again — I can't

say it often enough — to the effect of things when you are looking at

the whole picture. Anything is important which increases the effect of

light and shade. That light streak on the tablecloth for instance

emphasizes the shadow which the instrument casts across the table.

"Always

keep in mind the direction from which the light is coming, and the fact

that objects are casting their shadows across the table, even if barely

perceptible. That will help you to select the things that are of

significance.

"You are still thinking of things in terms of objects rather than in terms of areas of light."

"If you find a thing is going badly, go back and make more strongly the effects of light and shadow.

(Still-life)."Describe

the lights and shadows of the drapery in masses. Pay special attention

to the direction of folds in relation to the design. Invent if

necessary. Draw carefully and don't make fuzzy places. Where the edge of

the table disappears into shadow, don't make it plain. The light on the

edge of the table is important because it describes the kind of

material that covers the table. Yours might be a blanket."

Me: "Why do my watercolors lack a certain spontaneity and directness."

F.W.B.:

Because you don't look at things with their large aspects of light and

shade. As a design, not as objects. If you do this, you will get the

objects afterwards. No one who was not born with the ability to do this

can achieve it without a constant effort of will. If a landscape is not

worth painting purely as a design in light and shade it is not work

painting at all, unless by the addition of a wave or a rock or an

interesting form of some sort. Those pretty colors mean nothing without

good drawing and an interesting design.

"I simply

follow the light, where it comes from, where it goes to. In the

beginning make an artificially simple division of light and shade. Of

course, light has very subtle variations - it wouldn't be interesting If

it hadn't - but do not make them in the beginning. Get the large forms

right by the simple light and simple shadows. Don't fuzz It up and

soften the edges and lose the characteristic forms of ???, etc. In the

clothes you aren't sure just what you see in the large forms, so you

say, well, here is a wrinkle, anyway, I know where that is, and you put

it in and spoil all the large effect of the mass of light as

distinguished from the mass of shadow. You haven't made the shadows on

the white collar a part of the whole shadow, you are too anxious to keep

it looking white."

"You must be entirely absorbed by

the light and shade. You must turn right away from what has been most

important up to now - drawing -and put down merely what the eye can see.

Look for the places where the outline is lost and paint those most

carefully. Because that is very difficult to do, don't yield to the

temptation to draw a line around things. That (Mother's silver pitcher -

this was at 14 Chestnut) is very beautiful, lovely to paint. But it is

beautiful because wherever you put it, - there are places you can't see,

that lose themselves against the background. In arranging a still-life

you are carried away by the beauty of the things themselves, instead of

arranging them so that light is beautiful. Don't paint anything but the

effect of light. DON'T PAINT THINGS."

"You still won't

believe me when I tell you that the light on the whole figure is far

more important than anything else you can do (any details) In giving the

reality of the thing."

(Landscape). "Look at the

shapes of the lights and shadows, put them down flat, make them exactly

the shapes they are, without detail, and leave them. Don't puddle around

with leaves and branches. Make the shadows right in relation to each

other- near in value - and only when you have that done right, put in

details. As much or as little a3 you like. That is not important.

(About

a still-life with a vase of oak leaves). "I see very clearly the

simplicity of the way the light falls, and yet the drawing is terribly

complicated. As long as you try to make it better by improving the

imitation of things, you will get into trouble; paint the light only.

The drawing of the drapery gives the texture.

DESIGN

"There

never was a great portrait which was not great because of its design,

its arrangement or the whole figure and canvas, rather than just the

face. The face is important too, but much less so than the whole. Few

understand this, and because there is a face, think that is why they

like a portrait. ----- paints only the face and so will never be

successful in making a good portrait—paints the mask only and disregards

the design. No one can be told what design means, but must feel the

need of it and learn through experience. I never realized its importance

until I was In my 30's— had an intuitive feeling for it before. When I

realized it I enthusiastically organized a class in design at the

school and tried to teach the students something that I never had had

taught to me. They didn’t know what I was talking about.

"A

picture is merely an experiment in design. If the design is pleasing

the picture is good, no matter whether composed of objects,still life,

figures or birds. Few appreciate that what makes them admire a picture

is the design made by the painter.

"The important part

of a still-life is the design. Just so long as you are working on it to

improve the design the picture is going ahead."

(Apropos

of some photographs of places, I asked why it is that things dim; seen,

in a mist for instance, seem much handsomer than those seen in detail.)

"Simply because it allows you to see the design and does not distract

your attention with unimportant small things."

"You

will always get into trouble unless you design all the time you are

painting. Stop designing and you are in trouble. You are so fascinated

with painting, with making the things to look like reality that you

forget to design. The things themselves should be made only at the very

end —till then concentrate only on the values, and relations of color

and space.

"You should look at a landscape — here's a

way to get yourself into the right frame of mind — as if you were going

to decorate a plate, to make a pattern that would successfully decorate

that plate, and use the landscape before you to do it."

(I

said I did not like the way my paint looked when it was on) "That has

nothing whatever to do with it. Any more than what kind of ink I use in

etching. The only way to achieve the kind of effect you are trying for

is to get the right point of view toward the whole thing. Then you could

put on paint with your finger and do better than you do now. You will

never get what you are after until you arrive at the purpose that is

behind it. You have a certain sense of design, but you don't use it when

you sit down before a landscape. You try to paint what you have seen

other people do and to make it look like rocks and trees instead of

Using it as a design. The great value of simplification in design is

something you don't yet understand.

"Design makes the

picture. Good painting can never save the picture if the composition is

bad. Good painting - representation of objects -is utterly useless

unless there is a good design. That is the whole object of painting, and

unless you can think in those terms, you will never be a good painter.

That is why painting is bad for you, except as practice in

representation. You will not learn to be a good painter by doing

portraits. You are too much interested in an eye or a nose, in the

likeness.

"People who write about painting rarely know

what a painter is trying to do. It doesn't matter whether you use

landscapes, or birds, or people. Try to fill your space with the best

possible pattern. Only intuition will tell you what is right. Men have

tried to do it by mathematics. The Greeks had a feeling for it like no

other people since.

"A

picture is good or bad only as its composition is good or bad. You

can't make a good still-life simply by grouping a lot of objects,

handsome in themselves. You must make a handsome arrangement, no matter

what the objects are. Remember the clipping of a still-life of a

disorderly table desk with papers, a hat, etc."

(We

were talking of how the same principles of composition seemed to apply

in all the arts, and FWB told me of a conversation with his friend

Charles Martin Loeffler, the composer.) "We were sitting in front of the

fire and talking of pictures, which he enjoyed and appreciated very

much. Loeffler asked me to describe to him what went on in my mind when I

was In the process of composing a picture. I tried to tell him as best I

could, and went on talking I suppose for half an hour. At the end of

that time I said: "I don't know why I am going on like this, for it

can't mean much to you." He leaned forward and put his hand on my knee

and said, "My dear Frank, I am greatly moved by what you have told me.

3y changing a few nouns, that might be a description of exactly what

gees on in my mind when I am composing a symphony or an opera."

This

was to emphasize, again, the fact that it is the composition, the

design, the creation of the artist's mine, which is important, not the

representation of objects with paint. "I grew up with a generation of

art students who believed that it wa3 actually immoral to depart in any

way from nature when you were painting. It was not till after I was

thirty and had been working seriously for more than ten years that it

came to me, the idea that the design was what mattered. It seemed like

an inspiration from heaven. I gave up the stupid canvas I was working on

and sent the model home. Some men never discover this. And it is to

this that I lay the fact of such success as I have had. For people in

general have a sense of beauty, and know when things are right. They

don't know that they have but they recognize great painting. And design

is the ONLY thing that matters."

THE WHOLE

"Paint

in a tentative way - not as though you had to paint a picture of the

fabric to sell it to someone. The reason for the effectiveness of such a

way of painting is that you are painting a light, a value, in relation

to the whole picture - not just by looking at that exact spot and

painting what you see, which is what you do. That fold Is not

interesting in itself. But it is interesting to paint because of what it

does to the whole picture. You are still interested in too small things

- an ear, an eye, a likeness, that Is the worst thing, a likeness. It

takes your,, attention from the whole picture. But you have to have it,

of course.

"Paint a shadow where it comes, don't fuzz

it up. Then when it is dry, if necessary do the small things. Did it

ever occur to you that you could make things look lighter, not by using

more light paint, but by making a sharper edge where the shadow comes?

Paint exact shapes." (He takes mixed paint on the brush, held loosely by

the end, and drags it over an area that needs light or dark, leaving

irregular edges, slowly and carefully - modifies it, if necessary by

another brushful of darker color dragged over it. As different as

possible from mixing a lot of the same' color and slapping it on.

"Tentative." And the effect is miraculous. More like nature than the

most meticulously painted area. And glowing with light and color. He

says it is because he is putting down values in relation to the whole

picture. That does not explain it. To me.)

"Look at the picture as a whole all the time you are painting it.

"Look

at a head (or a landscape) always as a whole, as a head and not as a

collection of features. If you look at one feature alone you will not

make it in proper relation to the whole. Don't draw lines around

things—make them by rendering the light and shadow.

(About

a still-life.) "It is perfectly possible, with all those handsome

things to paint to go on making each thing better and better and at the

same time to have the picture grow worse and worse. The reason it looked

well at the beginning was because in order to get the thing laid out

quickly you had to make everything flat and simple. Don't paint each

object for itself, separately, but as a part of the whole. Paint the

Biosphere, in which all the objects are, and in which they have their

relations to each other. Don't fuzz things up, and mess the paint

around. If it isn't right, pushing it around and blending it in won't

make it so. Scrape it off and put in something that is right, drawing

the shapes carefully. But at all times observe minutely the delicate

variations of value between one thing and another or between the light

and shadow. Do not paint the figure, the rabbit, the Instrument — paint

the light and shade and interrelating values of the whole thing."

"A

picture is always a synthesis, never forget that. Made up, it is true,

of analysis—it must be. But the synthesis is what is important. Choice

is what matters. It may not be conscious choice, but what seems natural

and inevitable to the painter. This makes a distinguished sketch, or

picture. Distinction cannot be achieved by "spelling words" — by doing

each half-inch meticulously and perfectly. Never do anything without

regard to expressing the whole, the spirit. Your drawing must be better

than pretty good. It must be distinctively done.

"Do

not look at one spot and paint that exactly. Look at the whole thing.

Look at the head, and see at the same time what value and color the

landscape is, and upright of the screen.

"Paint in a

tentative way - not as though you had to paint a picture of the fabric

to sell it to someone. The reason for the effectiveness of such a way of

painting is that you are painting a light, a value, in relation to the

whole picture - not just by looking at that exact spot and painting what

you see, which is what you do. That fold Is not interesting in itself.

But it is interesting to paint because of what it does to the whole

picture. You are still interested in too small things - an ear, an eye, a

likeness, that Is the worst thing, a likeness. It takes your,,

attention from the whole picture. But you have to have it, of course.

"Paint

a shadow where it comes, don't fuzz it up. Then when it is dry, if

necessary do the small things. Did it ever occur to you that you could

make things look lighter, not by using more light paint, but by making a

sharper edge where the shadow comes? Paint exact shapes." (He takes

mixed paint on the brush, held loosely by the end, and drags it over an

area that needs light or dark, leaving irregular edges, slowly and

carefully - modifies it, if necessary by another brushful of darker

color dragged over it. As different as possible from mixing a lot of the

same' color and slapping it on. "Tentative." And the effect is

miraculous. More like nature than the most meticulously painted area.

And glowing with light and color. He says it is because he is putting

down values in relation to the whole picture. That does not explain it.

To me.)

AND RELATIONSHIPS

“Look

at the whole scene constantly. You are too anxious to complete the

thing instead of trying to see it right. You have got to give up what is

easy and attractive (and natural, too) to do, and simply try to see the

relations of values. A skilful man will seem to be making things at the

same time, but really if he is good he will be only painting "the

relations of things. You think you do, but you have got to do it

entirely differently if you are to get a real effect. Careful drawing of

shapes is not making things.

BIG LOOK

"You

are always making things too complicated. Looking for small variations

and little reflected lights. The trouble with most women is that they

soften and prettify things and so lose punch. Don't make it look right

near to — make it look right twenty feet away. Keep a flat tone over all

that background, edge on to the light, with a solid figure in front of

it.

VALUES

"You are paying too

much attention to getting different colors in the background. Colors

don't matter much--values are what you must get right—they are the only

things that give any effect of sun and shadow. Don't mess around with

your color and pat it down and smooth it out. Put it on and leave it.

And make it "strong." You can't exaggerate too much—in the house it will

all tone down and look too feeble. If a thing looks pinkish to you,

make it vermilion. Don't be afraid of making things too strong. Draw

very carefully the fine shape of a handsome tree or object. Take plenty

of time and draw it well. Not easy to do.

(Concerning a

portrait). "Don't draw the hair with strokes of the brush or make

ringlets. Make a flat mass of the correct value, and lay on the lights

drawing carefully the exact shapes. The light on that black hair must be

cool. And don't paint it with black paint even if it is black. Against

that green background It must have a certain warmth. (The model was not

present) ."The things that are important are the correct relations of

one thing to another—the hair, the shadow, the reflection, the

half-tones, etc. Until you have these values right it is absolutely no

use going ahead with anything else.

(Sketch of Mother

on the piazza). “Composition, Drawing, Values, Color, Hot local color,

Edges. Above all, values. How the light falls. Keep comparing everything

else with the darkest spot. With the lightest. Draw shapes carefully

-that is not finishing. Don't paint objects. Paint only values.

"When

you don't know what the values are, you make It fuzzy, try to fix

something that's wrong by doing something more wrong. If you can't make

sharp edges between the values, they are wrong ... By making a sharp

edge between the light and shadow, here, the shadow does not need to be

too dark.

"Scumble it with white or black if a thing goes wrong and start over.

LOST AND FOUND

"

I am going to talk to you about something I have told you many times,

and you don't know anything about. You over-represent things. You should

be looking for the places in the picture where you can't quite see

things, and paint those the way they are. Choose a subject with those

places in it. Look at that face and then at the shoulder. Compared to

the head you can hardly see it. You make it that way and the head will

suddenly stand out. In your effort to get the features and likeness, you

make everything alike, and immediately everything loses its force. I

don't mean things are absolutely vague, but relatively vague. Try it. No

one can understand it 'till it happens to them.

"If

that head wasn't there, you'd have a darned hard time telling what that

coat was. Well, make your coat just as hard to see. This is something

people never get told in school. It shows in all your work, landscapes

and everything.

COLOR

"When we

speak of color, we do not mean colors, such as the green of leaves or

the pick of cheeks. We mean the effect of light on an object, and the

effect which one color has on another nearby. No relation to what the

ordinary person calls color.

(Still Life.) "You don't

keep your lights flat enough. That is flat yellow light right up to the

edge, not fading away pinkly at the bottom. And you will not get an

effect of light unless there is more warmth In your shadows. I don't

know whether I see the colors — I think I do — or merely have learned

that things must be that color in order to have the necessary effect. I

sometimes think I have no sense of color, as people mean it.

"When

most people talk of color, they mean colors. What I mean is not the

local color of any object but the relative value of light and shade.

Warmth in the shadows. It doesn't matter whether a model has a colorless

face — there is color in the contrasts of light and shade. Don't make

your shadows so slatey. When painting the drapery don't make it in

carefully modeled stripes. (Drapery at the top of the picture). Look at

the center of the arrangement and then notice how much of the folds you

see-practically nothing, just a vague light here and there. Paint it so.

"What

gives charm to a picture is not the brilliant color—the strong

contrasts, but the delicate bits, where one thing comes against another

with no difference in value, and only a slight one in color. This is

what is hard to do, and hard to see. Only a trained eye can see it. But

the doing well of these bits is the most essential part of making an

interesting picture. What makes the difference between a good picture

and one where only the obvious differences are put down is how these

delicate, intimate details are made." (This is as near as I can

remember, and frequently repeated.)

WARM AND COOL

"The

difference between warmth and coolness gives the true colors. See in

the shadow there, behind the figure (still-life) there are lots of rich

colors. But look away from it and you will see that it is all very vague

compared to the figure itself. But vagueness does not mean fussiness,

it means a very narrow difference between the different values. Paint it

crisply, but keep it well in the background.

"Put down

things strongly that indicate the nature and character of an object.

Look for the significant things. Don't paint and model each little

detail, (of the drapery) but put down in proper value and warmth or

coolness of color the salient and characteristic lines.

"When

you notice that one color is cooler or grayer beside a warm shade it

does no harm to intensify the color of that spot as you do with effects

of sunlight.

NEUTRALS

"A real

artist is constantly looking for, searching out, the places in a picture

which are not brilliantly colored. The neutral colors—Tarbell calls

them the dirty colors. Without them, the rest lose their effect. A

picture all bright colors loses the effect it would have if there were

in it these contrasting bits of dull color. They are not noticeable in

the picture, but they are what makes for Its effectiveness—something

that people not painters think is made in some magical way.

DRAWING

"Drawing is only learned by long hard practice. You can't learn it quickly, and you won't learn it quickly."

"Drawing can be learned — a sense of color must be born in a person").

"You

are beginning at the wrong end; no one should begin to paint until he

is able to draw well. Drawing is always hard. You always have to work at

it, even after forty years(said in a discussion of Jacobleff's work).

“Get

rid of all that purple molasses. You draw things light-heartedly and

slap on paint. It would take anyone two hours to draw that branch

properly.

FLATNESS

"Lay the values in flat.

"You

haven't painted long enough to know what "flatness" means. It Is the

most valuable quality there is. You see a mere breath of difference in

value, and you put In all sorts of changes and modulations."

''You

don't know what flatness means. When that is dry, scratch on a few

lines of paint over it to make that place lighter. Get It flat.

EDGES

EDGES

"The

most important parts of a picture are where edges meet, or one thing

comes against another. Anybody can paint the rest of it. Edges must be

very carefully studied. If there is no defined edge, don't make one”

Don’t make edges meet. Paint one over the other. A sky with variations

of light and dark and especially a light or a dark line around the edge

of objects simply spoils all effect of reality.

"Don't

make a thing inconspicuous by making it fuzzy." (difficulties with the

background). "Make it flat in tone, all over, and it will stay back.

Never make fuzzy edges, unless it actually is fuzzy, like the back of

the hair." (portrait)

DETAILS

(About

outdoor painting.) "Don't fuss around with all the details until you

have your masses in and your composition arranged. The important things

are the edges. The contrast between the hard sharp outline of branches

against sky with the soft edges of shrubbery and foliage.

"If

you make things right in the order of their importance you will never

get into trouble. This business of fussing around with the details

before you have gotten the masses in correctly is what makes for a poor

picture.

"Do not make the unimportant parts of the

picture in detail, only do as much as you can see when you are looking

at the main theme of your picture. Don't make so many different values

and colors. Decide on what you want. Mix It. Try it. Mix it again if it

is wrong. Then put it on flat and leave it. If you can only do a small

part of the canvas, do It right and leave It that way."

"The

reason you got into a mess with that picture is that you get fascinated

with details and forget the main things. You had to have because you

had gotten into a state that you couldn't have gotten out of alone. Now

you have gone ahead in the right way." (The help consisted mostly in

blotting out and blurring what I had done, leaving the plan and the

drawing but obliterating the details, giving me a chance to start fresh

and repaint the lower part of the canvas.)

THE MAJORS

People

who paint cheap things do it by modeling the pieces. People who paint

good things seem to do it without modeling. If you put on a pure value

there, right up to the edge of the shadow, it will seem to model. Don't

paint square inches, paint large masses.

TIGHT V. LOOSE

"We

used to talk about "loose" and "tight" methods of painting

when we were

young. There are only a few people - Lucas Van Leaden,

Holbien, for

instance - who can paint as tight as a drum and still have

it good; and

that is because they look at it in the same way I am teaching you. And

they are able to paint in that manner and still not lose

the effect."

(In

answer to my question as to the explanation of the effectiveness of

"loose" painting.) "Because it admits the varying qualities of the

unseen. Literal description inpainting will never make a picture. In

order to be good it must have some touch of that magic which gives the

effect of light and shade, leaving undescribed the places that are dim

and cloudy, and painting sharply the silhouetted values."

PRACTICE

''Do

carefully and well what you do. If you haven't time to finish a sketch,

make what you do count. Don't hastily rub it in just to cover the

canvas and say to yourself you will go back and do it better

later—that's lazy, and besides it never looks the same.

LAY-IN

"A

head which is to look right when finished, in the early stages of

blocking in the lights and darks, ought not to look right; it ought to

look raw, crude, almost violent. Then all the qualifying tones will not

spoil its strong effect of light and shade when it is finished.

WET INTO WET

"Never

leave white spaces around the edges of things. That absolutely ruins

any effect of reality whatever. Beginners always make that mistake.

Don't paint two things up to each other, paint one on top of the other.

Sargent always said to paint the background of a head half an inch

inside the outline of the head, and then paint the head on top.

"Where

trees look thin, don't put a thin wash of color on over the sky. Decide

what the value is and they lay it on with plenty of paint.

PAINT QUALITY

Don't

paint with soup, paint with paint. You will never get any effect of

color without using lots of paint and very little medium.

"One

of the most interesting times in my painting life was when Tarbell and I

saw some pictures in Boston by a European artist— I've forgotten his

name — who evidently got his effects by using a very "full" brush. We

decided from that time on to use only a very full brush in all our work.

The effect is produced because you carry your color, or value all

across and it does*not thin out at the edges, but keeps it full effect

everywhere." (This still does not explain to me why this method of

dragging a full brush loosely across an area, leaving a more or less

broken surface of color, is so effective.I said it gave a certain effect

of texture, but he said no.)

PAINT HANDLING

"Sergeant

was said to "dash" his paint on to his canvas. It is good practice

(apropos of working from a model) to make a sketch by mixing your paints

carefully, studying your model carefully and then lay the paint on

where it should go and don't touch it again. Never puddle around and go

dab, dab, dab. Scrape it off if-it is wrong and lay on some more. But

don't pat it and blur it and try to remedy it by blending it with

something else.

STUDIO CONDITIONS

"Its no use trying to paint under unfavorable conditions. It’s hard enough to paint with everything just right.

STRENGTH AND DELICACY

(When

I said that my finished portrait looked "soft") "It is very difficult

to make the right adjustment between strength and delicacy. Both are

important and one must not be allowed to spoil the other.

ATMOSPHERE

"Colored

moving pictures do not attract me because although the local color is

there, the subtle variations of light and reflections are missing. Those

are what make any scene In nature attractive to the eye, although the

casual observes does not realize it. When one has analyzed it with the

eye of an artist and tried to paint these very subtle variations he

appreciates them, they are what makes the picture

good, what gives it an

atmosphere, and must be painted very delicately and with nice attention

to the minuteness of the differences. Although not at all obvious in

themselves, if well done they make the success of the picture.

STUDY

"There

is a saying that there is nothing more to be found in a picture by the

beholder than has been put into it by the painter. The more a painter

knows about his subject, the more he studies and understands it, the

more the true nature of it is perceived by whoever looks at it, even

though It is extremely subtle and not easy to see or understand. A

painter must search deeply into the aspects of a subject, must know and

understand it thoroughly before he can represent it well. The bald,

obvious aspect of a picture are not the interesting ones. That is why

the public will never understand painting. They admire it, yes, and like

it, but will never understand it because they cannot understand what

goes into the making of It. They ascribe all sorts of motives and ideas

to the painter—none of which he ever has—because they can't understand

how he thinks."

INSPIRATION

"Those

things which you do when you are freshly inspired and excited by the

beauty of what you are seeing before you are important things. If you go

back to them later and think you will improve them by making them

carefully, slicking them up, you will lose that important thing and

there is no method of getting it back. It is gone for good. Let things

look rough, rather than try and smooth them out. There Is a certain

inspiration which comes when you work quickly and surely and

enthusiastic about the beauty of the light. You should leave this work

and go back to it later to realize how good it is, and that it must not

be painted over. Get the force of the light.

AND POETRY

"A

picture or drawing is like a poem, when the poet starts, he has no more

and no different words to work with then you have. A work of art is

made by his choice — selection and combination of ordinary material.

Each man sees a subject differently and selects different things in it

to emphasize. See any roomful of student's drawings."

LANDSCAPE

( When I asked how to get the effect of a mass of bare tree branches against the sky)

"The

general mass effect is darker than the sky, even than the pieces of sky

seen through them. So don't draw a faint tracery of branches against

the light value of the sky—you'll get no effect that way. Put on a flat

tone just faintly darker than the sky and then indicate a few darker

lines against that.

SUBJECT

"The

trouble with you is that like most beginners you try to embrace too

wide a scene. You are looking for the sort of scenery that a

photographer would look for with lots of sky and distant hills. Be

broad-minded and don't go out with a pre-determined notion of what you

want to find to„ paint. Intimate studies of light and shadow in a small

area are most Interesting. A thing to be beautiful must be complicated.

Don't paint something bad just because it is simple. It's just like a

tailored suit—the thing must be subtle In order to be good. The fine

distinctions of value where one object comes against another are what

make a picture interesting. When Sergeant went up to visit Billy James

at Chicora, they went out painting and Bill led him along without saying

anything, and took him unobtrusively to the "town view", mountain

reflected in lake, etc. Asked him if he thought he could find anything

round there to paint. Sergeant said yes, he could find something

anywhere, looked around him and sat down and painted an old gnarled root

with, some leaves and branches on it. What interested him (and F. V.

3.) was the delicate play of light and shadows on the leaves and trunk.

"Whenever

I find myself—as I do sometimes—painting a "scene" I am disgusted with

myself. Take a small piece of something with a handsome shape—don't

include too much. That tree trunk against the cedars veiled "by the thin

underbrush in front. Don't take in the branches against the sky, that

gives a second center of interest."

"In looking for a

subject don't look for a grand panorama but a near thing with

interesting lines and values. DON'T PAINT A SCENE.

GOOD PICTURES

"A

good picture has a certain austerity, a distinction, whether of the

thing itself, the lighting, the color, or the arrangement. Mere

craftsmanship, representing nature, does not make a picture.

MODERNISTS

(Speaking

of modernists)" That is what the most honest of the modernists are

trying for. The plain fact does not interest them. They say "I will not

say D-O-G spells dog, because that is stupid and literal. So they make

something else, liberate themselves to say the same thing in another,

more interesting way. But the others, less honest, merely look at the

fact of liberation, do not understand what they were liberated for, and

merely think they can make anything and call it Art. They are not happy

about it, don't enjoy what they do, so says J.P.B (John Benson).

"The

modernists think they are Inventing something new every day. Men's

minds don't work that way. Every invention is based on completeness. You

might say I invented something. I merely noticed and painted an aspect

of nature that had escaped other men's observation. Now there are

hundreds of men who do the same thing, more or less well, according to

their real knowledge."